Traversing Boundaries:

The Sculptural Evolution of Hsu Yunghsu

Chia Chi Jason Wang / Independent Curator and Art Critic

Even a brick wants to be something.

A brick wants to be something.

It aspires…

—Louis Kahn

Hsu Yunghsu (b. 1955) is a rare and unique figure in the Taiwanese and international art scenes.His sculptures stand out because of his profound understanding of materials, distinctive techniques, and innovative style, making him an unconventional yet extraordinary master.

He says that by chance, he founded a ceramics studio with his friend in 1987. Before that, besides being a full-time elementary school teacher, he mainly focused on painting and had been an active Chinese zither (guzheng) musician. Unfortunately, due to rheumatoid arthritis, he had to end his17-year-long career as a professional performer.

It is hard to imagine that Hsu started out with no background knowledge in ceramics. He taught himself everything through He taught himself everything through sedulous study and hard practice.It wasn’t until 1992 that he entered the studio of the well-known ceramist Winnie Yang (born in 1946), obtaining advice for a limited period. For a long time, he remained an amateur artist. In 1998, he made the decision to leave his teaching job of 22 years only three years away fromretirement. He then fully devoted himself to the art of sculpture, making him a late bloomer in this field.

During the 1980s and 1990s, ceramic art in Taiwan was generally referred to as “craft”, with most creations focused on functional vessels, especially practical wares for daily use. Deeply influenced by China’s longstanding ceramic traditions, artists often dedicated themselves to perfecting the intricate and exclusive glazing techniques that defined their work. Between 1990 and 1993, while still in an exploratory phase, Hsu Yunghsu has shown little interest in producing utilitarian objects. Instead, he preferred pure forms, incorporating symbolic elements rooted in classical Chinese cosmology. He also used the surfaces of his abstract sculptures as canvases for his paintings.

From 1994 to 1998, Hsu Yunghsu’s early style began to take shape. He returned to the natural color of high-fire clay and worked primarily on the theme of dancing couples, creating forms that balanced between the abstract and the figurative. The bodies, moving with the melody of music, appeared soft and showed the graceful rhythm between dancers. He saw the stage and theater as metaphors to express life stories. Over time, the elegant human figures became more stylized, evolving into sophisticated, intertwining abstract loops.

Since becoming a professional artist in 1998, Hsu entered a brief stylistic ambivalence. That same year, the Council for Cultural Affairs (now the Ministry of Culture) introduced the “Regulations on the Installation of Public Art.” This policy opened up vital resources and provided exhibition opportunities for Taiwanese sculptors who had struggled for recognition. It is unclear whether Hsu’s formal adjustments and stylistic shifts during this period were directly related to these developments. However, what is certain is that, beyond his existing expressive abstractions, he made a dramatic return to figurative forms—not realistic, but conceptually simplified, with a noticeable presence of figuration. The works are rendered mainly on the frontal view. Full-bodied or deliberately fragmented standing or seated human figures quickly became his new mode of expression. Judging by the titles of his works, there are implicit references to social status and power. Notably, in 2000, he created several large outdoor figurative sculptures exceeding two meters high, with some even exceeding three meters. Their scale was already close to that of monuments.

However, he quickly shifted from monument-like figurative forms back to abstraction. From 2001 to 2004, he created an extensive series of works under the title “Myth”. The viewer may find it difficult to grasp the narrative, as the transformed human figures continued to flow between the figurative and the abstract. At the most extreme, he simulated the melting state of material forms, turning them into indescribable, shapeless fluid objects. In his 2007 artist statement, he explained that, unlike before 2001 when he mainly expressed his views on the external environment, later personal life changes led him into a chaotic phase, redirecting his focus inward. From this perspective, the fluid imagery in Hsu’s work during this period seems to reflect metaphorically his personal life experiences. As his sculptural figures became increasingly abstract, it was as if hesaw his works as projections of his inner mind.

Looking back at Hsu Yunghsu’s early creative practices before 2004, his works were primarily

driven by notions and emotions. Their expression aligned with his social perspectives and inner state. If they did not reflect his thoughts on life or social phenomena, they acted as a mirror or projection of his inner self. As a creator, a person is shaped and influenced by their living

environment, educational background, and physical and mental structure. However, if art, especially sculpture, merely serves as a simplified representation of the creator’s limited personal state, it risks becoming superficial and formalized. At this stage, Hsu seemed to have become aware of this issue. From 2003 through 2007, while studying for his master’s degree at Tainan National University of the Arts, he experienced a significant transformation in his creative approach.

The year 2005 represented a defining watershed moment in the evolution of Hus Yunghsu’s artistic journey. In the spring of that year, he traveled to the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) in New York State, where he participated in an artist-in-residence program. During that period, he visited Dia Beacon, where he encountered firsthand the works of American Minimalist and Post-Minimalist artists—an experience that left a profound impression on him. Particularly, the uses of materials by Richard Serra (1938–2024), Michael Heizer (born 1944), and Fred Sandback (1943–2003), the spaces that their works have created, and the way they stimulated and activated the viewer’s physical perception prompted him to gain a new dimensional understanding of sculpture.

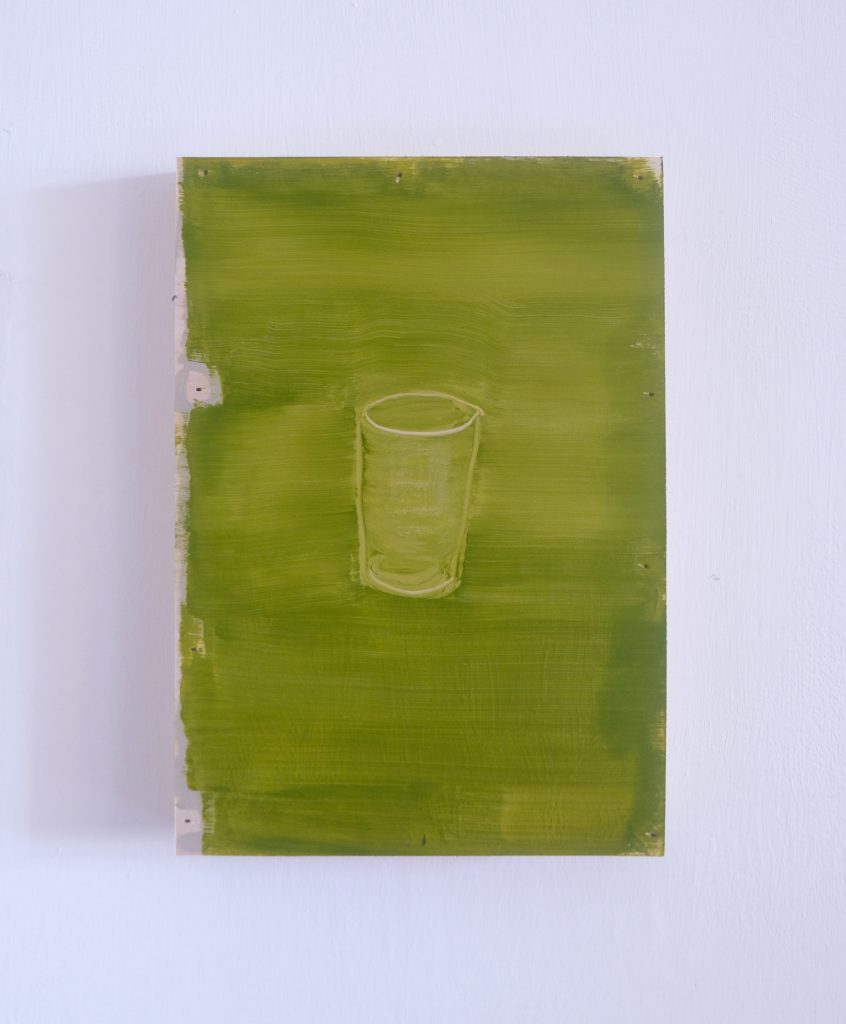

During Hsu’s residency in New York, the pressure of creation made him anxious. Without realizing it, he began kneading a ball of clay with his fingers, shaping what he described as “objects resembling cups or boats without any intended meaning” and “the extremely thin forms spread out toward the edges, where they appeared broken.” This seemingly unconscious action unexpectedly opened a new artistic dimension for him. The key was not the cup-like or boat-like object he had sculpted but rather the process of kneading, pressing, molding, and shaping. Through these motions, he momentarily let go of his attachment to established forms and styles. By immersing his body in the clay, Hsu Yunghsu reconnected with the essence of materiality, unlocking a new approach to sculpture.

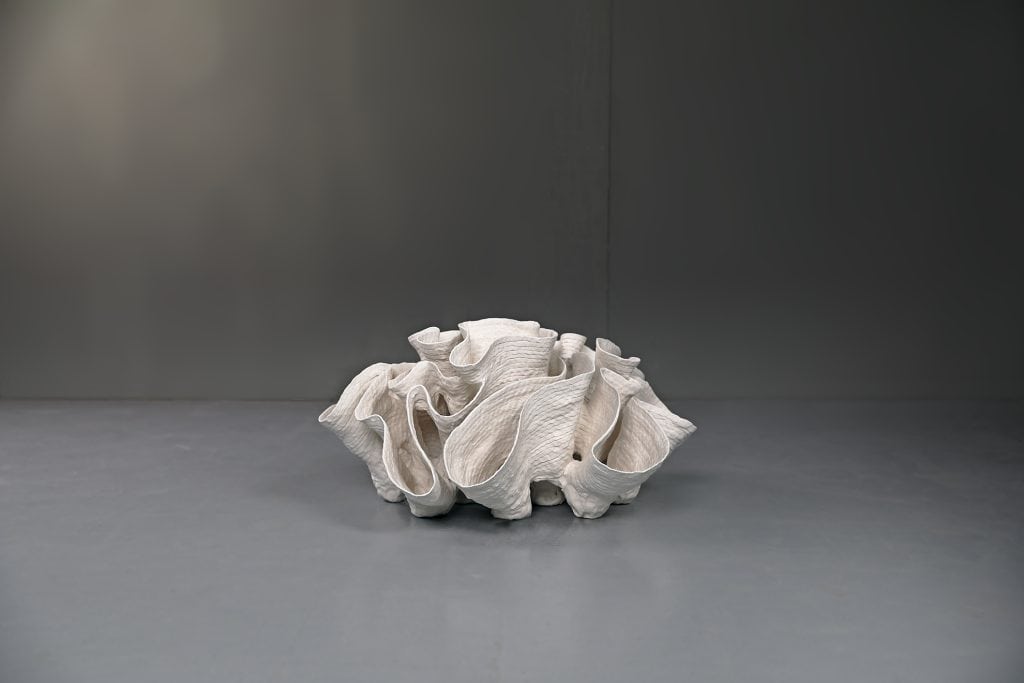

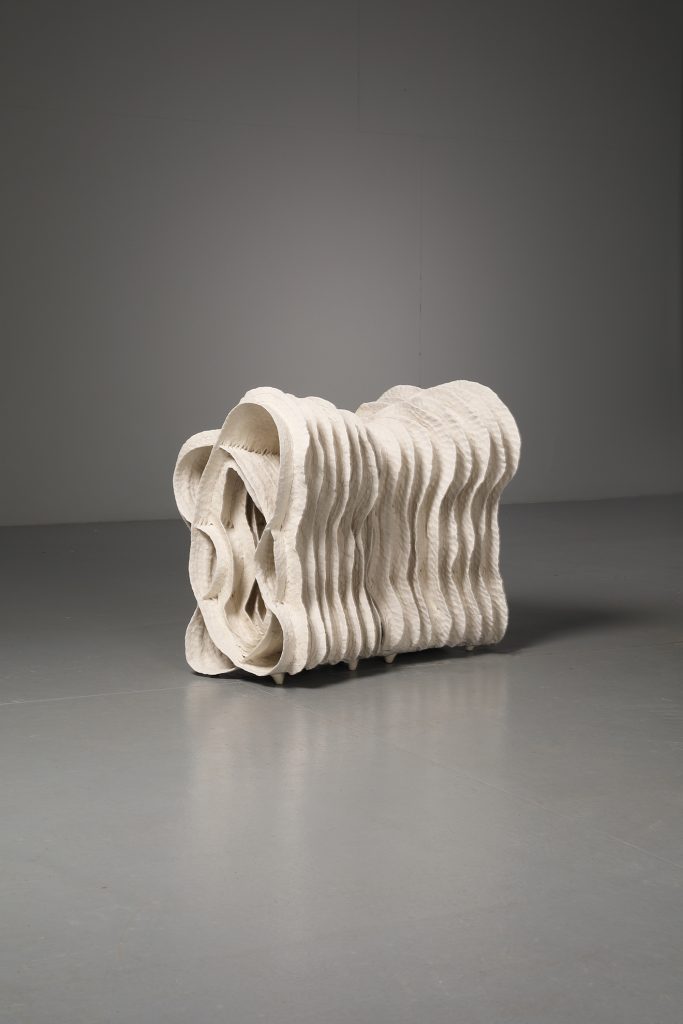

As his creative thinking and methods evolved, Hsu Yunghsu’s works took on a completely different appearance from his earlier pieces. The year 2006 marked the beginning of his later innovations. He used his own body as a sculpting tool, never relying on others or mechanical assistance. Starting from the ground or a tabletop, his hands moved back and forth repeatedly while his body shifted in and out of the space. He shaped soft, elongated clay strips into three-dimensional structures. This sculpting method closely resembles the coil-building technique used in the earliest potterymaking stages after mankind entered the Neolithic era. However, he was not imitating objects or any recognizable figurative forms. Instead, he followed the natural properties of the material, layering the coils to build irregular oval loops with undulating, wave-like shapes. After the ceramic firing process was completed, he adjusted the orientation of the works for display. For large-scale sculptures, he typically arranged them in a tall and upright position. As Hsu moved his hands and body in and out of the sculptures, it evoked an experience akin to traversing through a passage of time and space.

Renowned American architect Louis Kahn (1901–1974) once offered a poetic rumination on the brick—architecture’s most fundamental unit—reflecting on how it might fulfill the highest potential of its material nature. Hsu Yunghsu, in his pursuit of sculptures that are both large and extremely thin, not only relied on his entire body in the creative process but also had to test the limits of his materials. Before firing, ceramic objects exist in a soft clay state. Their size and structure are affected by both the natural properties of the material and the stress caused by gravity.

Additionally, firing at temperatures over 1,200 degrees Celsius introduces unpredictable factors that can cause the structure to collapse if stress issues are not solved beforehand. To ensure a high success rate, Hsu had to carefully control the firing conditions and reduce uncertainties as much as possible. He applied a scientific approach to every step, including selecting the right clay, designing the kiln, handling the pieces, balancing the gas flames, and maintaining stable kiln temperatures. Through years of refinement, he developed his own unique kiln-building and firing techniques.

Inspired by Richard Serra, Hsu Yunghsu’s works often remind people of Serra’s massive steel structures made through forging techniques. However, not only are their materials completely different, but their creative processes also follow entirely distinct paths. The key difference lies in how American Minimalist and Post-Minimalist sculptors moved away from working directly with materials, instead relying heavily on industrially produced components and outsourcing fabrication. Serra also depended on specialized industrial processes. In contrast, although Hsu designed his own kiln, he adhered to the traditional artist’s hands-on approach. Working entirely on his own, even at the cost of exhausting physical labor, he firmly believes in the unique beauty and spiritual strength that comes from engaging his body in the artistic process.

Minimalism challenged the expressive approach of Abstract Expressionism, rejecting the idea of artworks as direct reflections of the artist’s emotions. Instead, the artist’s presence was removed, and the work existed independently as an object, defined by its material essence, waiting for the viewer to step into its space and engage with it. From the perspective of material exploration, Hsu Yunghsu may share a similar attitude with the aforementioned American sculptors. However, his approach to art fundamentally differs. His works are infused with the sensitivity and energy of his own body, giving the sculptures distinct forms and expressions. Traces of movement—such as fingerprints and hand impressions—are visibly present, proving the artist’s continuous involvement in the process. American art critic Harold Rosenberg (1906–1978), in his analysis of Action Painting during the Abstract Expressionist era, wrote, “A painting that is an act is inseparable from the biography of the artist.” Through the imprints left in his sculptures, viewers can sense Hsu’s presence in the moment of creation. In this regard, Hsu undoubtedly aligns more closely with the type of action artist Rosenberg defined.

Hsu Yunghsu rejects formalization and avoids repetition, returning to the essence of materials and simplifying complexity while allowing natural hand movements to guide his creations. His works are abstract, with intricate and unpredictable structures—far from minimalistic. Perhaps due to his deep physical and emotional involvement, his sculptures create a sense of connection to the earth as if linking to the forces of nature. The planet itself is like an immense kiln, shaping rocks and minerals from the mountains to the oceans over time. This may be why his works evoke the feeling of natural creation. Hsu Yunghsu fully understands both the strengths and limits of ceramics, allowing him to push past obstacles and create breathtaking and dynamic sculptural landscapes.

▞ Exhibition Information ▞

Exhibition Period|2025.11.08-12.20

Venue|San Gallery・Kaikosha (No. 21, Gongyuan South Rd., North District, Tainan City)

Opening|2025.11.08 (Sat) 3:03 p.m.

Opening Hours|Tue – Sat, 10:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m.

▞ Series of Events ▞

11/08 (Sat) 15:03

Opening Ceremony of “Lūn-lūn”|Official inauguration of San Gallery Kaikosha

11/15 (Sat) 15:00

Artist Talk

Speaker: Prof. Tuan Tsun-Chen

Discussant: Artist Hsu Yung-Hsu

12/06 (Sat) 15:00

Conversation on Creation

Chen Huang-Yi, Museum Director × Artist Hsu Yung-Hsu

12/13 (Sat)

15:00 |Book Launch

Speaker: Mr. Lu Chieh-Min

Discussant: Artist Hsu Yung-Hsu

Special Guest: Architect Chen Chia-Yi

16:00|Book Signing SessionDo you like this personality?