Awakening the Wind: Lee Kai-Chen Solo Exhibition Breath in the Interstice

Text by Sophia Huang

The wind rises, wrinkling a long winter.

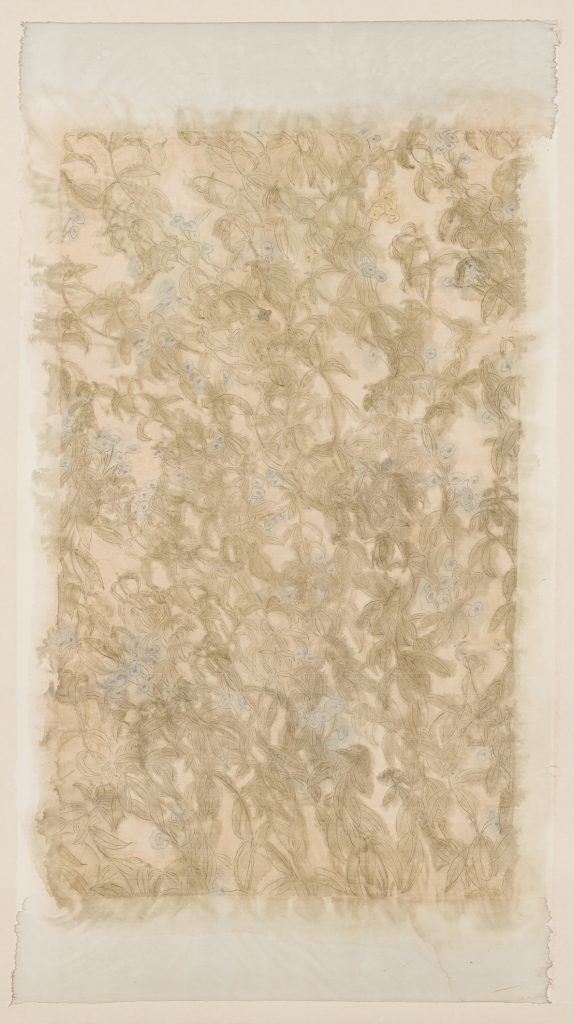

Along the edges of these creases, the contours of plants are cut out and embedded into the invisible fibers of everyday life, arranged into interstices that can breathe. The boundless wind flows like a river of ink, passing through bundles of fibers, slowly gathering.

The wind awakens.

Encountering Lee Kai-Chen’s works, for someone accustomed to breathing within literature—especially one long immersed in Chinese literature—there is an almost instinctive tremor. T. S. Eliot, in Tradition and the Individual Talent, wrote that a poet must possess both “tradition” and “individual talent.” The former refers to an active historical sense, a cultural consciousness that perceives the past and allows it to awaken in the present; the latter is the capacity to transform private emotion into an “objective correlative,” rendered through form and structure. A mature poet, then, is one whose talent awakens within the depths of tradition—much like wind gathering between fibers and within interstices. It is along these two threads, “tradition” and “individual talent,” that the following essay traces how Lee Kai-Chen awakens the wind.

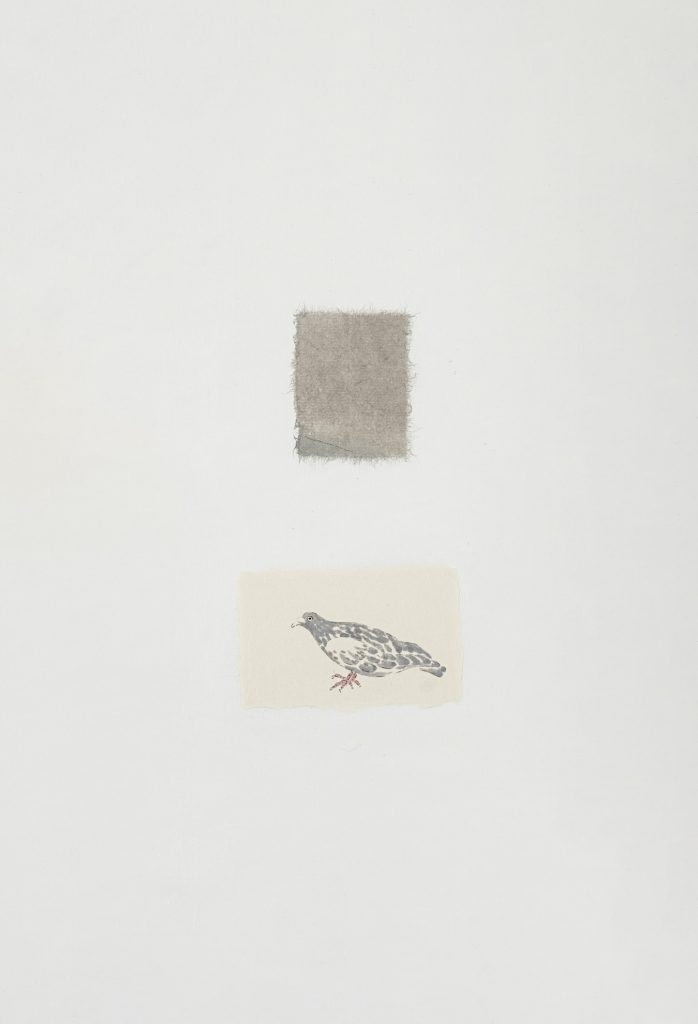

Many works in this exhibition are marked by expansive areas of blankness. As Liu Gangji(劉綱紀)observes in Five Topics on Chu Aesthetics, the people of Chu cultivated a distinctive aesthetic consciousness known as liuguan (流觀). In Li Sao(《離騷》), Qu Yuan writes of “wandering and observing above” and “surveying the four extremities of the world” (「周流觀乎其上」、「覽相觀於四極兮」), and in Ai Ying(《哀郢》), “I let my gaze wander in flowing observation” (「曼余目以流觀兮」). These are not acts of ordinary seeing, but of taking the entire cosmos as the object of aesthetic contemplation—seeking the infinite within the finite. This sensibility later crystallized in Chinese painting in two primary ways: first, the absence of a fixed viewpoint, giving rise to dispersed or shifting perspectives rather than single-point perspective; second, the use of blankness as background—not as emptiness, but as a spatial field of cosmic boundlessness. This resonates with the line from Chu Ci(《楚辭》), “The vastness of Heaven and Earth has no end; alas for the long toil of human life” (「惟天地之無窮兮,哀人生之長勤」), as well as with Yoshikawa Kōjirō’s(吉川幸次郎) reflections on sorrow born from the passage of time.

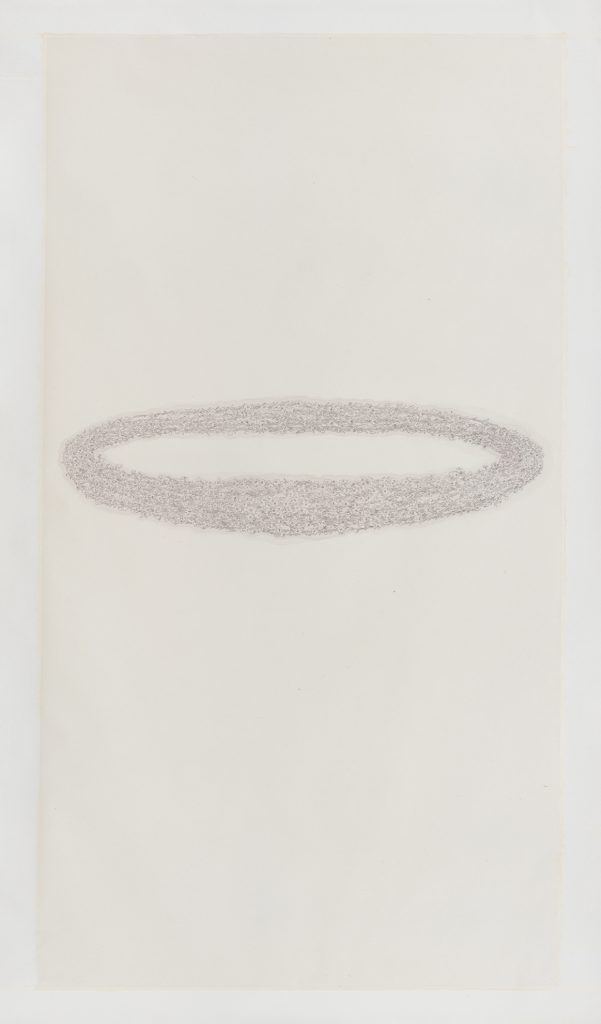

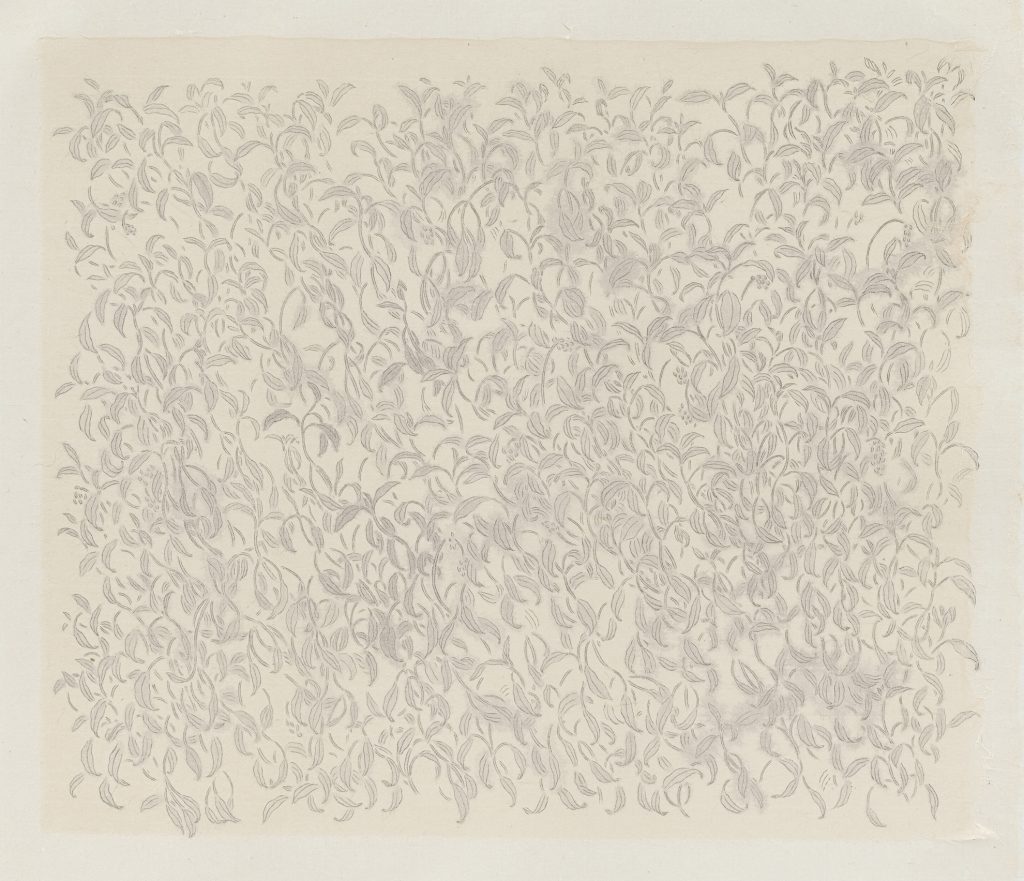

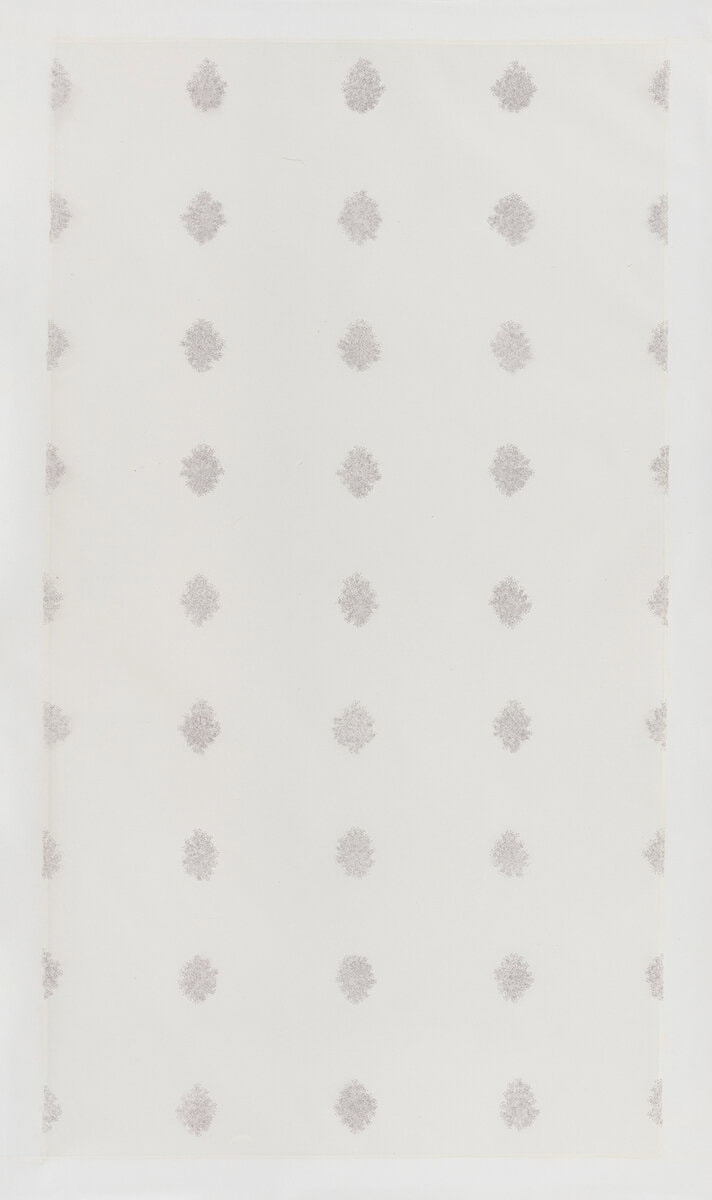

Yet neither Chu Ci nor Lee Kai-Chen’s works lead life toward despair. Rather, they carry an implicit awareness: within a finite life, every moment is worthy of being awakened by the wind. In The wind is boundless, the upper portion of the composition is left largely blank, the viewpoint unfixed, leaving only tree shadows and traces of wind below. Is this not another manifestation of liuguan? The blank upper field can become any space imagined by the viewer: a corner of a primary school yard in winter, where the wind rises, leaves rustle, children’s voices echo, and the soil carries a faint warmth; or a springtime alley, where the wind lifts the hem of a girl’s skirt, startling a dozing orange cat.

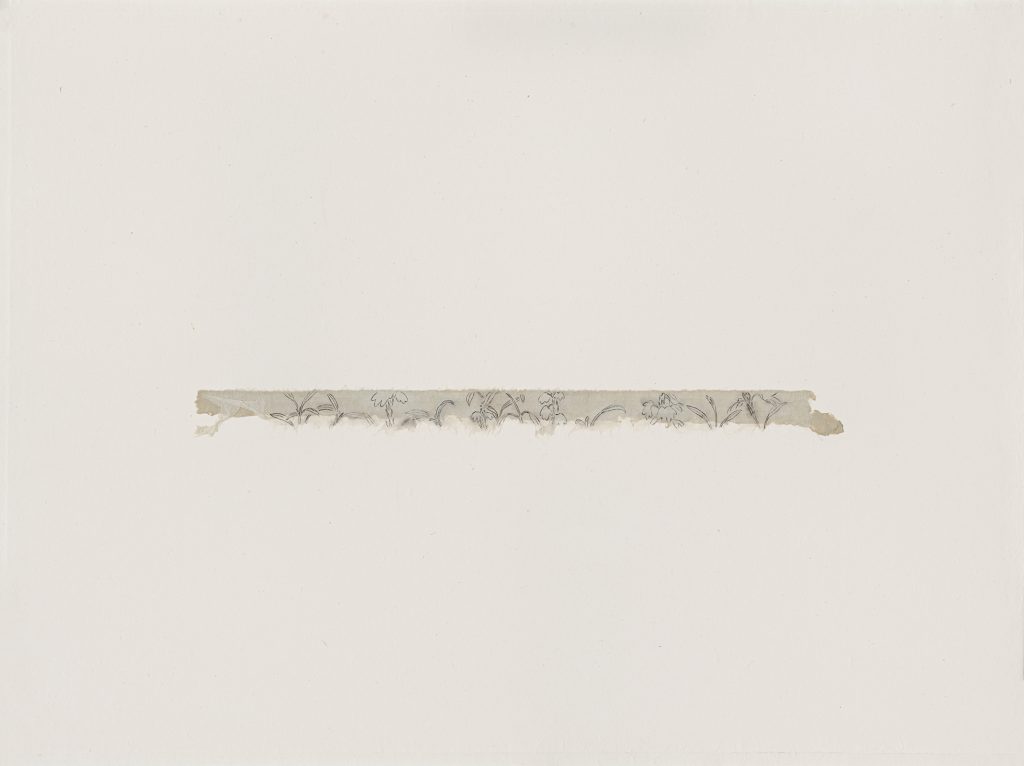

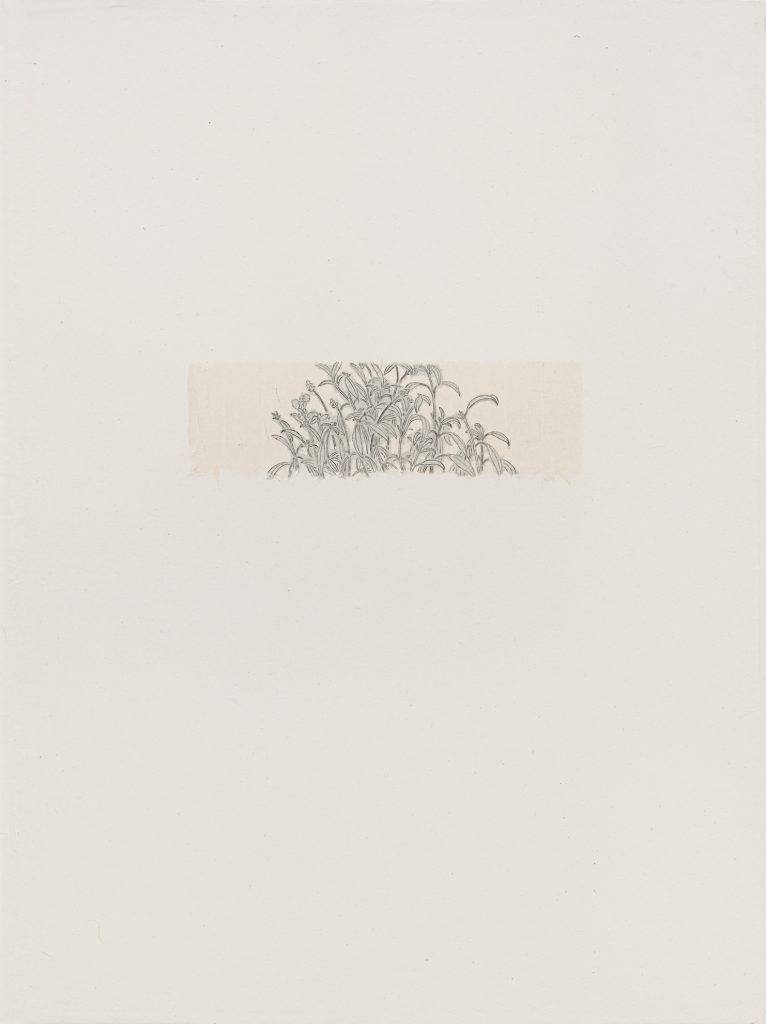

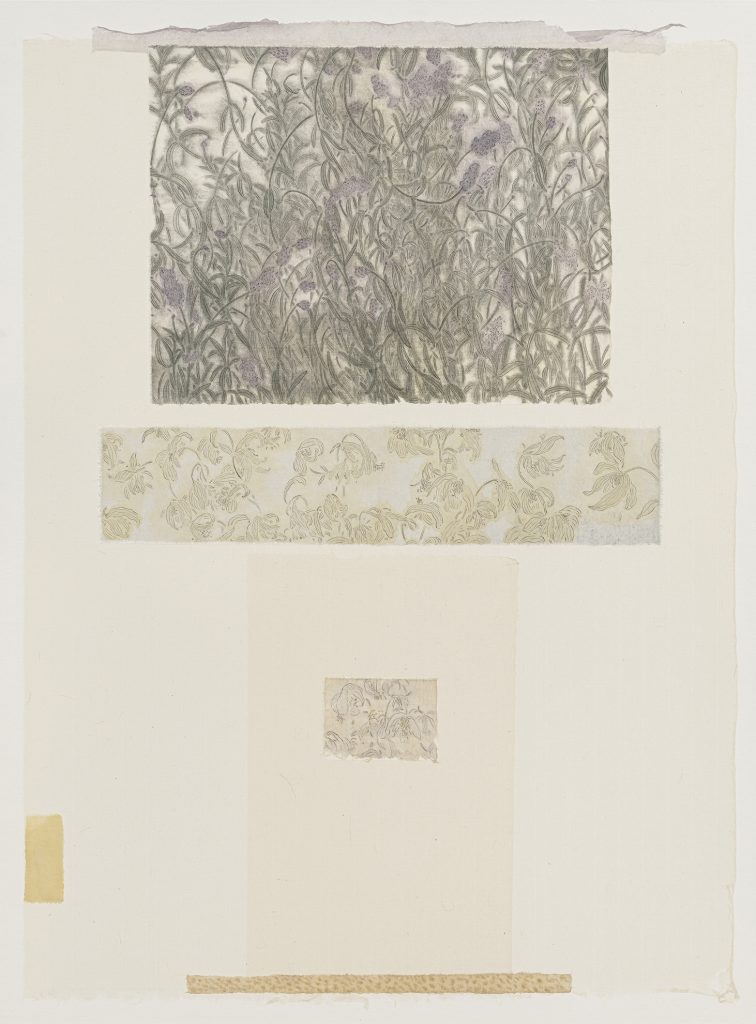

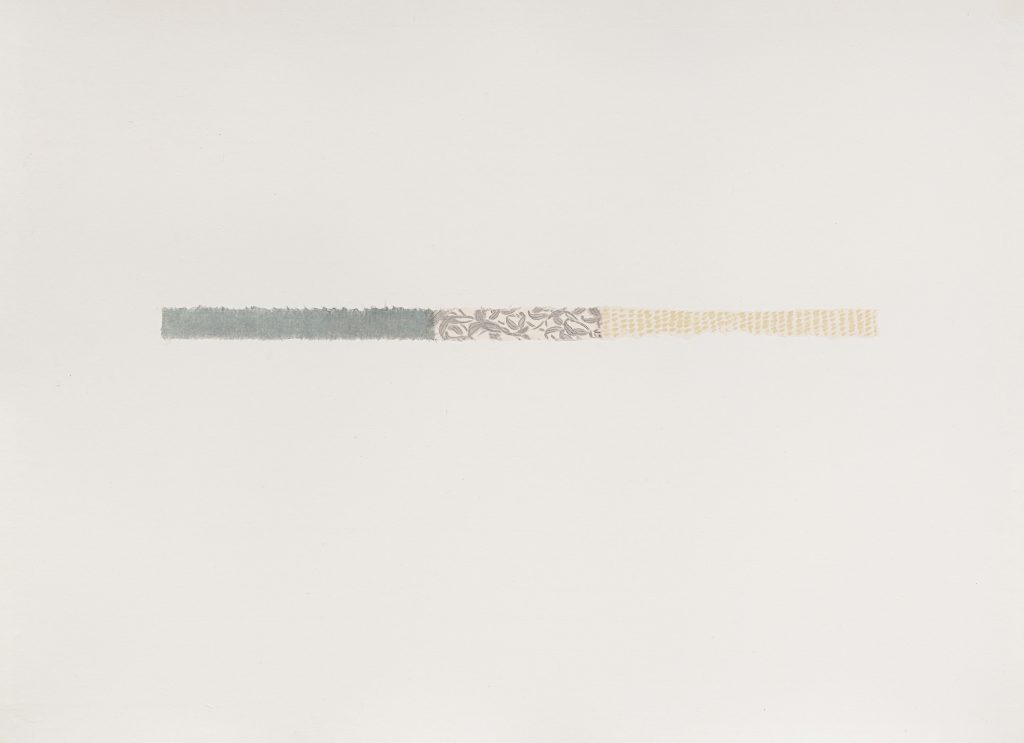

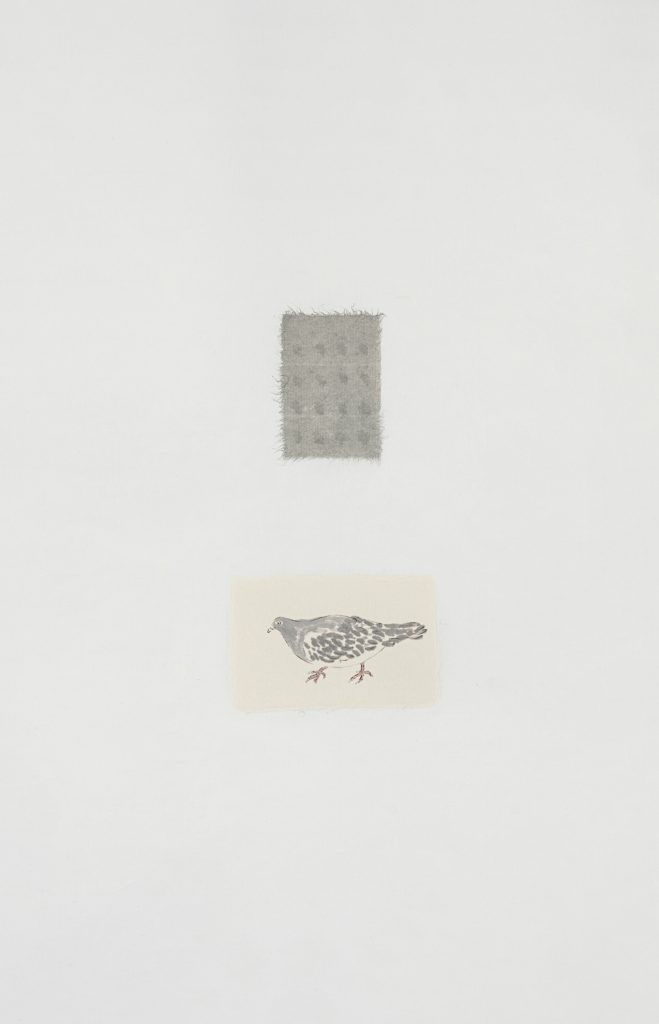

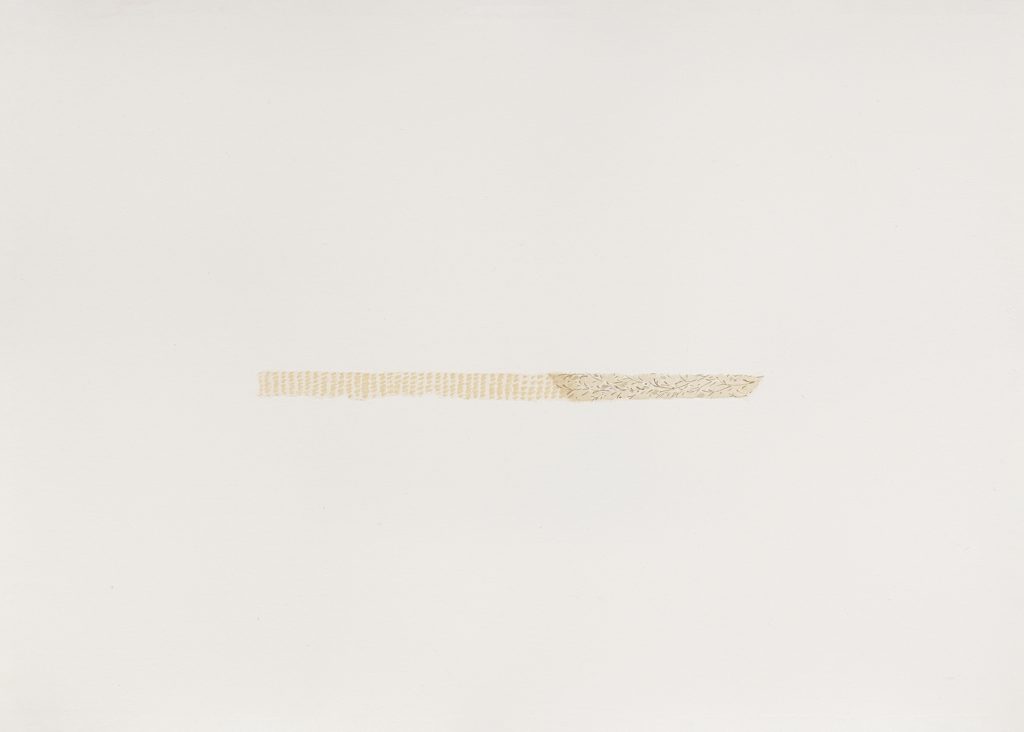

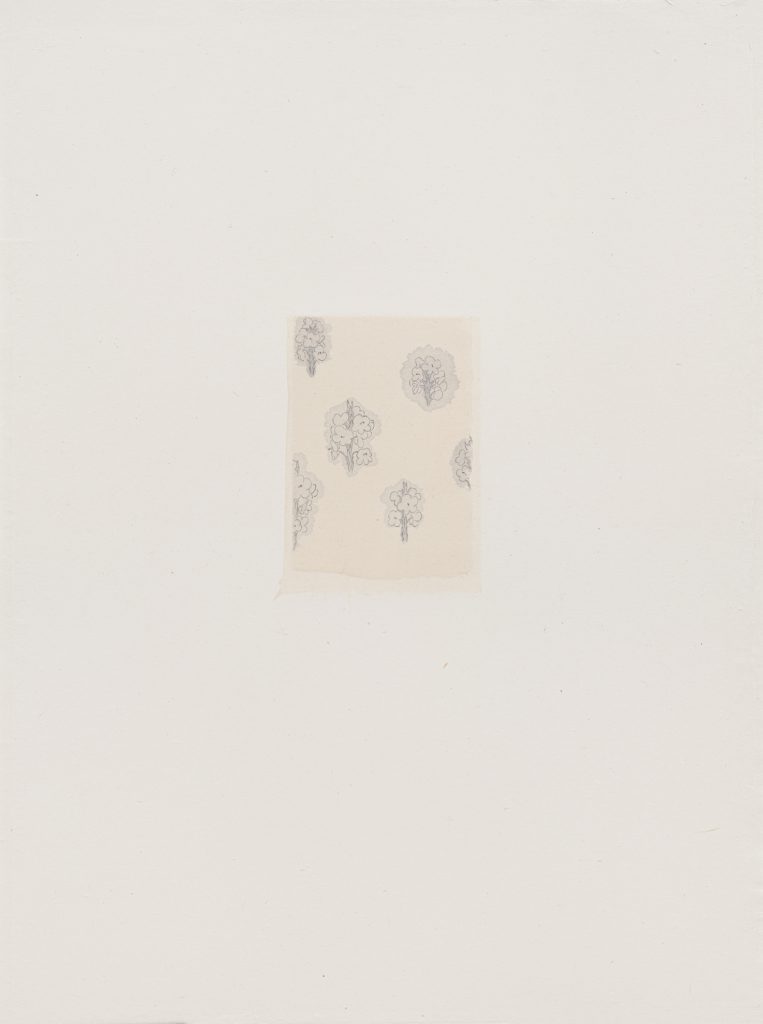

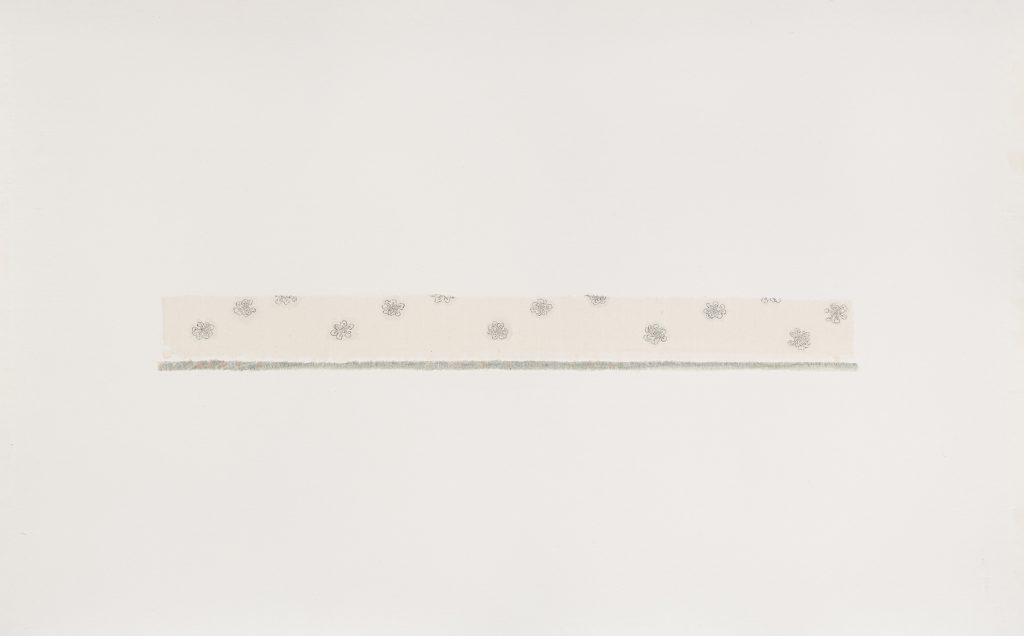

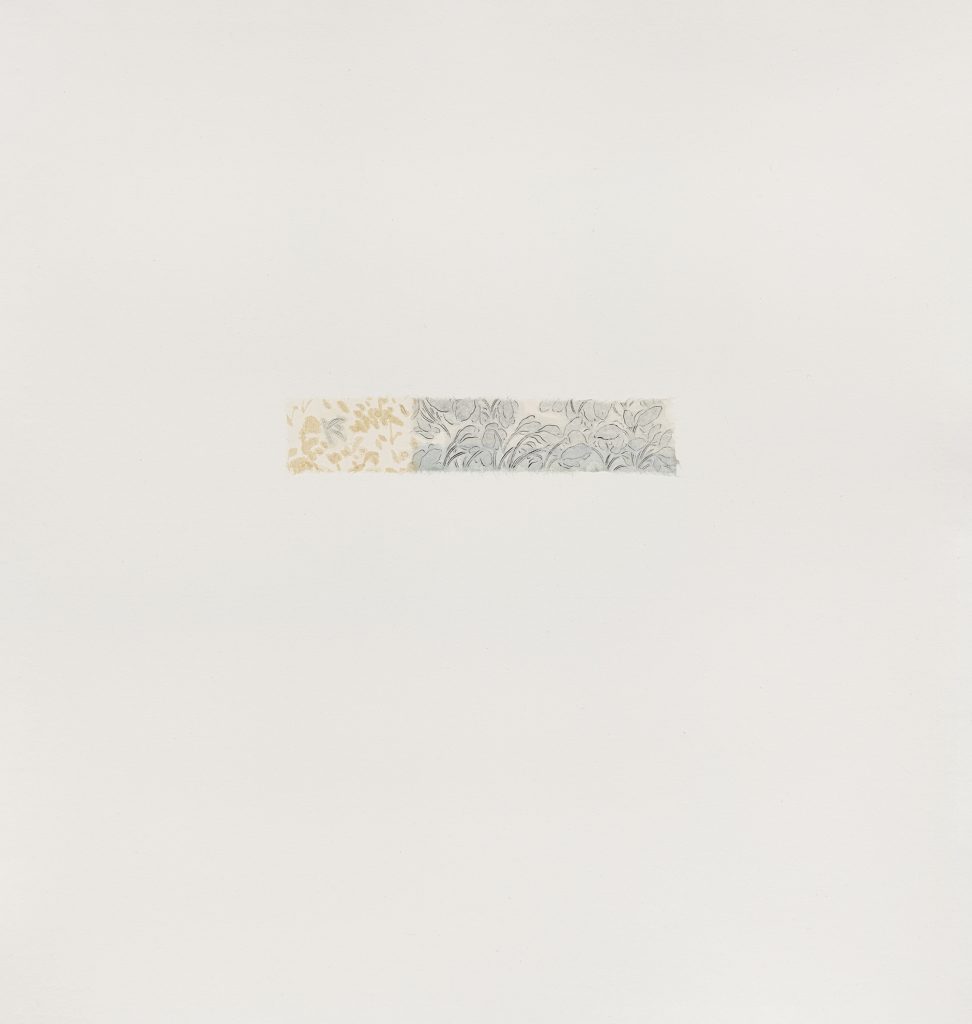

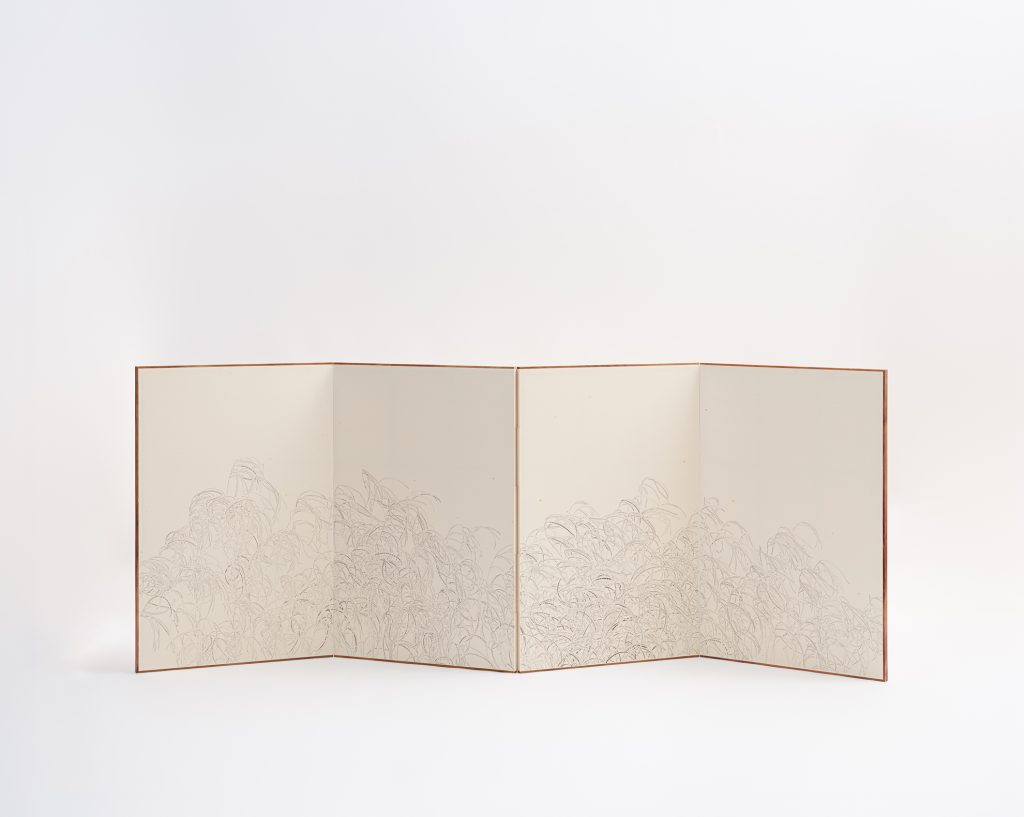

In works such as Long winter, The moment when things approach, and fold flowers, one encounters variations of blankness—arranged blankness and dimensional blankness. This is Lee Kai-Chen’s singular wind, awakened from within tradition. Unlike classical landscape painting, where blankness often occupies the upper register, the arranged blankness in these works resembles a microscopic scan: each interstice becomes a universe. Herein lies the meaning of the exhibition title Breath in the Interstice. Originally an architectural term describing airflow through narrow gaps, Lee’s English title suggests breathing within fissures—grasping infinity within fibers.

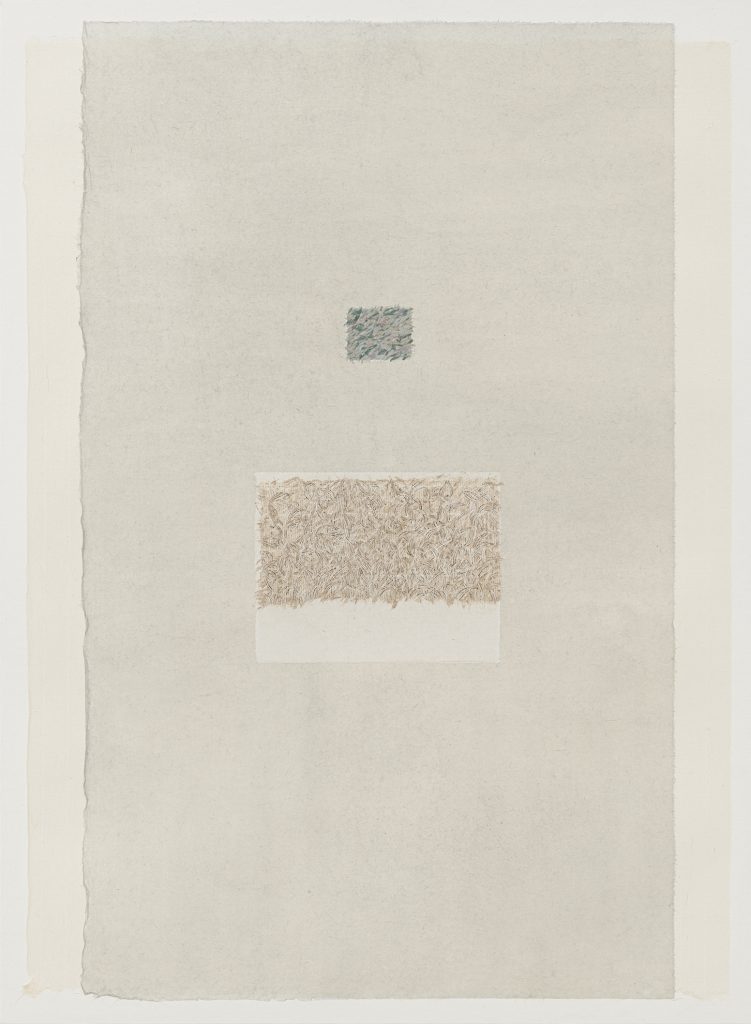

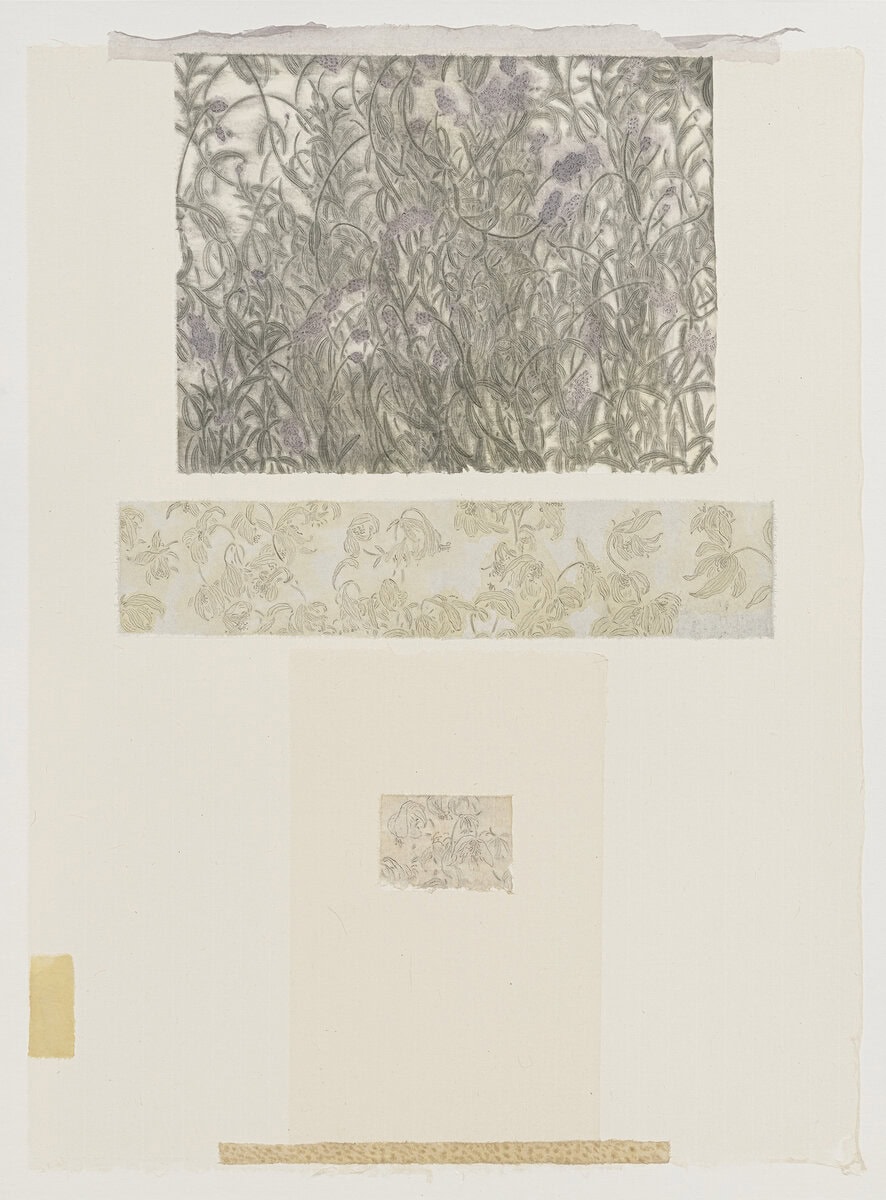

Dimensional blankness emerges through layering: one sheet for depiction, another for covering, like placing a veil of white gauze over the lens of a microscope. The instant is covered, its sharpness softened. Wind seems to be stored within the contact surface between two sheets of paper. If traditional blankness makes us aware of the existence of wind, Lee Kai-Chen’s blankness makes us aware of the moment of wind itself—no longer merely passing by, but being placed, gathered, and awakened.

Another thread emerges through the ancient formats of the handscroll and the painted screen. The handscroll, small and portable, invites an intimate mode of viewing, often revealed only on special occasions. To prevent fading, it is stored in wooden boxes: one imagines lifting the lid, encountering silk wrapping, unfastening the jade toggle, and only then seeing the work unfold. This viewing process is itself a ritual of time and space. As the viewer unboxes and unscrolls, wind passes through the fibers of paper, and when the depicted scene approaches, the everyday is awakened once more. In 2023, at A White Case at MUMU Gallery, Lee enclosed handscrolls within a box, fragmentary memories waiting for kindred viewers.

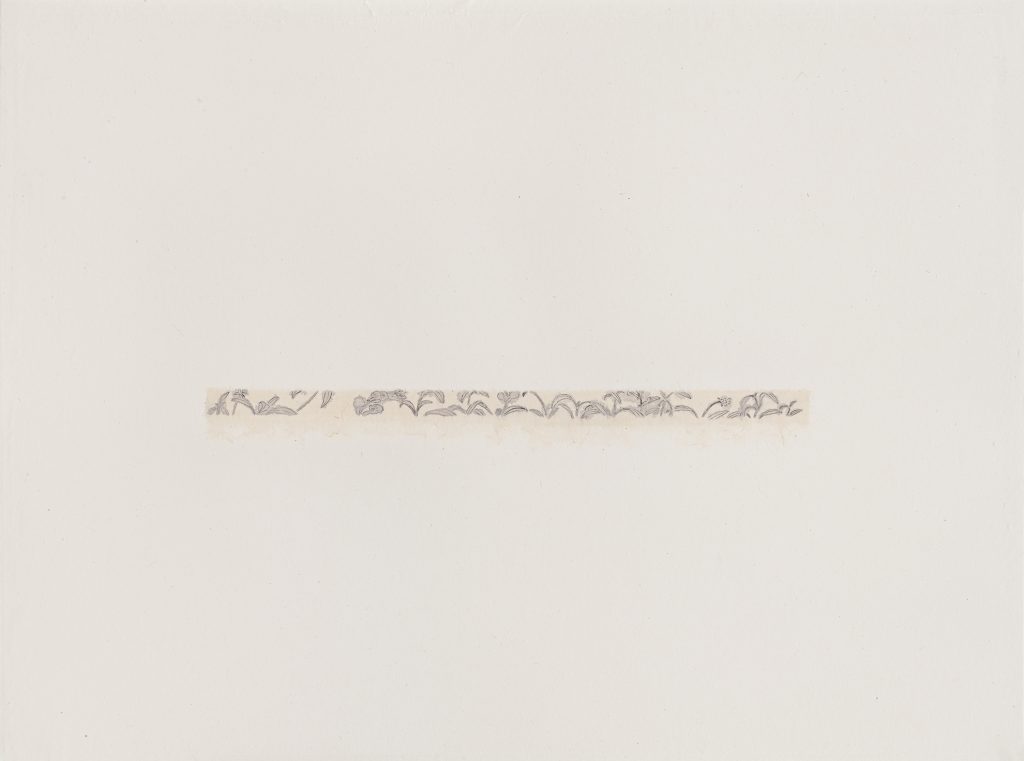

In this exhibition, however, she chooses to unfold them. The handscroll becomes a path for walking—spatial trajectories and temporal steps transformed into Road I and Road II. At first glance, one wonders whether the movement is upward or downward. Only upon a second viewing does it become clear: these are not routes but traces—no path, only the movement of sight. Extended through collage, rather than layered accumulation, Breath in the Interstice becomes the very trajectory of wind: elongated, irregular, boundless.

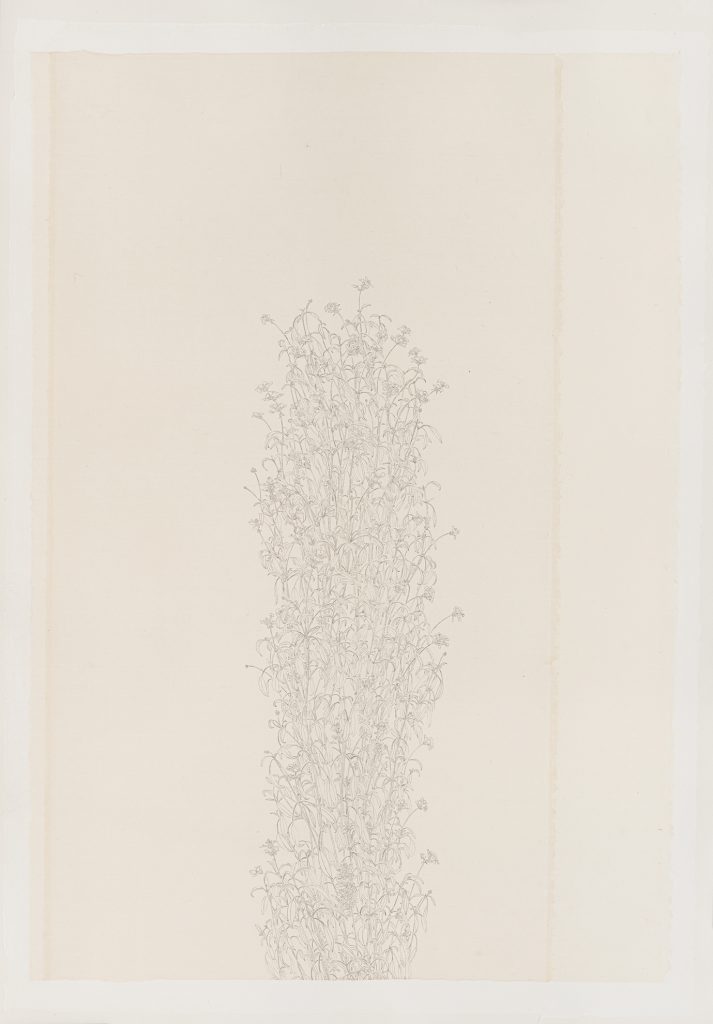

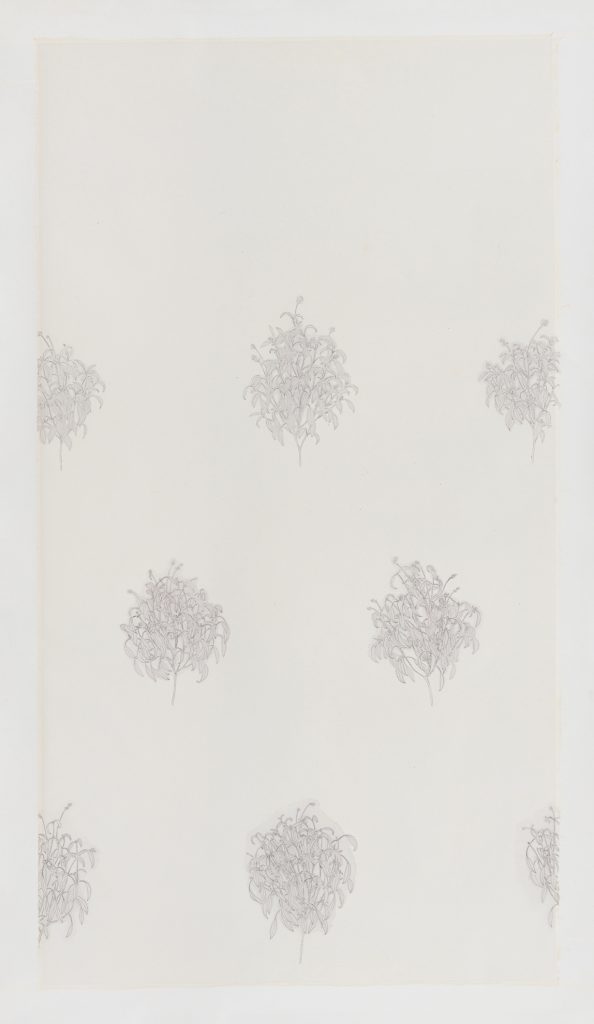

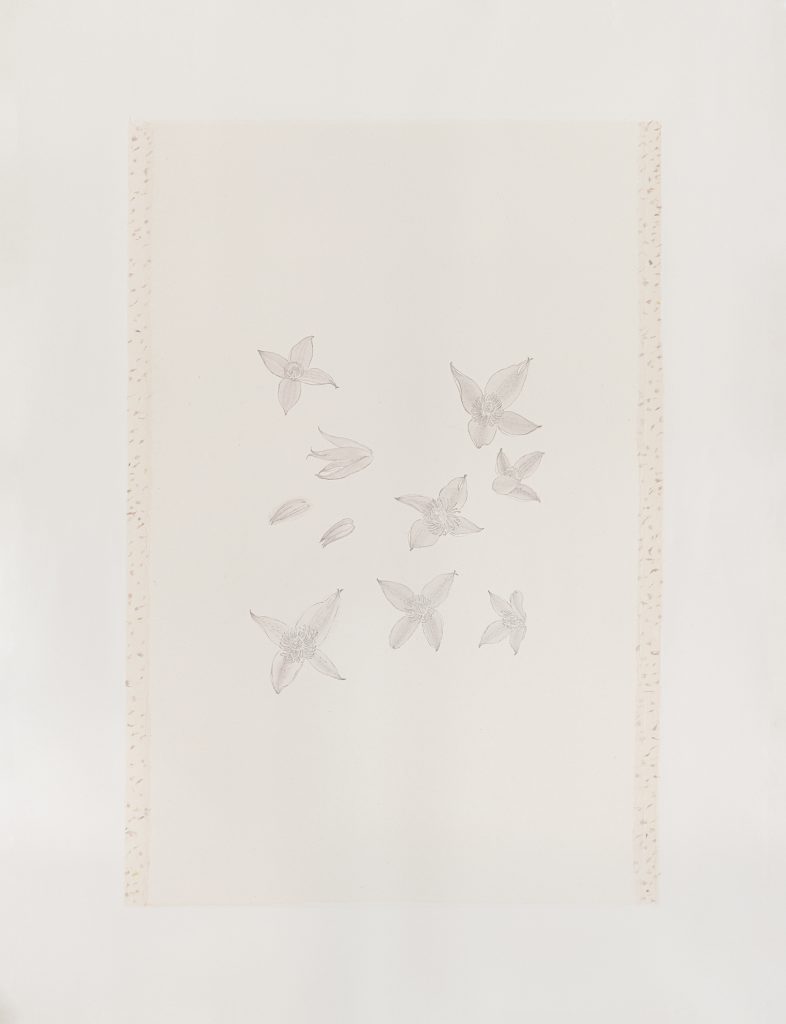

Bouquet I and Bouquet II take the form of vertical handscrolls, resembling everyday bouquets, yet they are not composed of fresh-cut flowers. Instead, roadside plants are gathered and bound in Lee’s own manner, forming singular bouquets. I am reminded of Qu Yuan’s extensive use of flora in Li Sao, especially the line “fragrance and dew are intermingled” (「芳與澤其雜糅兮」), followed by “yet pure virtue remains unspoiled” (「唯昭質其猶未虧」). In Chu Ci, plants symbolize moral integrity and serve as mediators between the self and the cosmos. And how does one perceive fragrance, if not through wind?

Here, I wish to note the resonance of the word “wind” in Chinese literary tradition. In Shuo Wen Jie Zi(《說文解字》), wind is explained through the phrase “when the wind moves, insects are born” (「風動蟲生」), capturing the principle that with the stirring of wind, all things come into being. Later scholars, in discussing the Chinese lyric tradition, often emphasize wind’s capacity for transmission—as a pathway through which emotion travels. Returning to Bouquet I and Bouquet II, I find that these two works awaken in me two currents of wind, leading me back to Qu Yuan’s fragrances and to other literary blossoms. Where fragrance exists, wind is present. At close range, the deckled edges of the paper rise gently, like fragments of wind left behind. Beyond those edges, the wind has already merged into the viewer’s everyday life.

Further on, I recall Wu Hung’s (巫鴻)observation in The Painted Screen: Chinese painting is rarely an isolated image, but is attached to objects—handscrolls, murals, screens. The painted screen, in particular, is both spatial and ritual. It divides, guides, and frames, such that in viewing a screen, we do not merely view an image, but also the ritual, the breathing of space, and our own position within it. This material quality is evident in The paper is dyed with flowers and blue and Because of the wind. Originally intended for personal keeping rather than exhibition, these screens found their place upon encountering the architecture of Kaikousha(偕行館). Wind passes through their seams, no longer confined to the image, but inhabiting the space itself.

The wind rises, wrinkling a long winter.

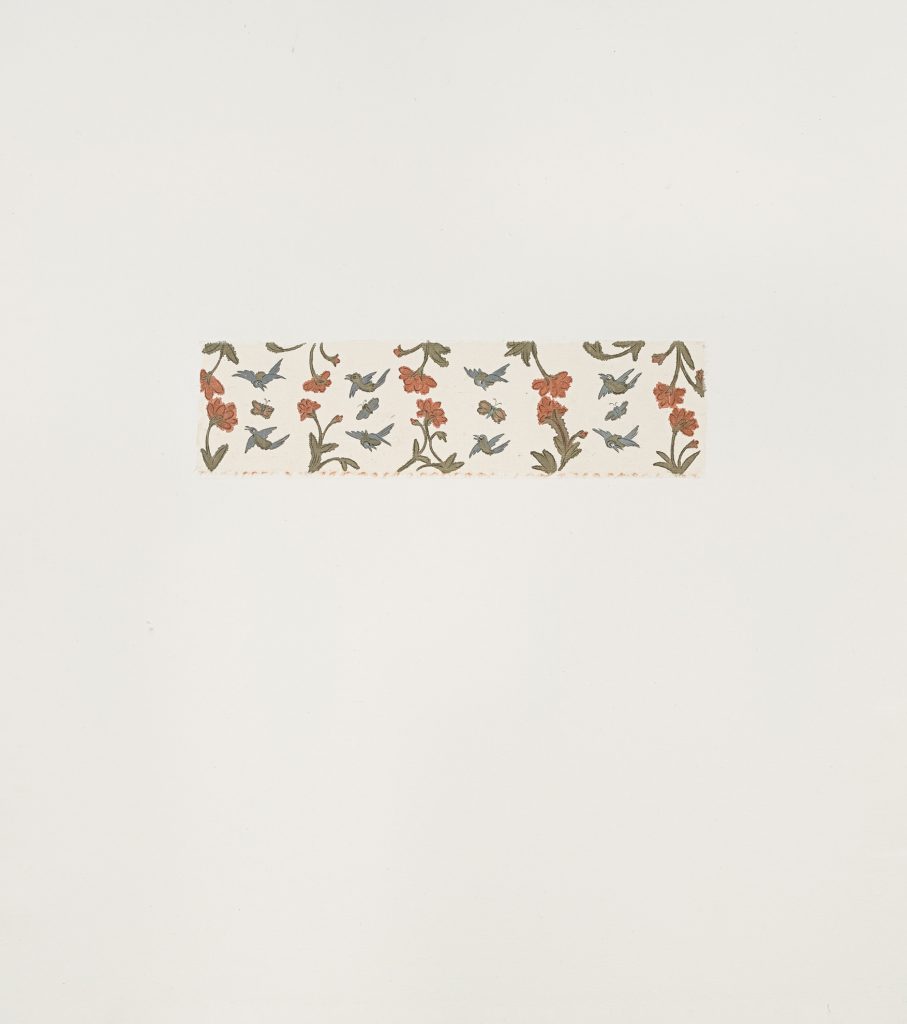

On an Ordinary morning, On the other side of the river, Because of the wind, The taste after the rain approachs. Butterfly birds and red flowers, Grey floor with pigeons.

Ah—The wind in the day

Awakened.

▞ Exhibition Information ▞

Title | Kaichen Lee: Breath in the Interstice

Exhibition Period|2026.1.3(Sat)-2.14(Sat)

Artist Talk | Kaichen Lee x Sophia Huang Jan. 03, 2026 15:00 – 16:00

Opening Reception | Jan. 03, 2026 16:00 – 17:00

Venue | San Gallery · Xiexing Hall No. 21, Gongyuan S. Rd., Tainan City 06-2208833

Opening Hours|Tue – Sat, 10:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m.