If I Were a Butterfly

Yuning Yang’s Solo Exhibition: “Petal’s Edge: Cutting into Spring”

By He-Ya Huang

Recently I returned to Wu Ming-yi’s (吳明益)The Way of Butterflies(《蝶道》). In its opening essay, “While There Is Light,” he writes: “To some extent, the world is established by light; without it, color and form lose their meaning.” I have long felt that visual art is always responding to light—not merely as something that makes objects visible, but as the very condition that allows seeing to occur. Light does not rest upon things. It moves through air, reflects from walls, pauses briefly along the edge of a petal.

Tracing Yuning Yang’s practice—from installation to painting—one sees how persistently light participates. It is both subject and collaborator.

Wu reminds us that butterflies do not see as humans do. Their visible spectrum is narrower; their colors less saturated. Yet they detect ultraviolet wavelengths invisible to us, reading the nectar guides inscribed on petals like secret maps.

And so an image rose in my mind:

Cold spring air.

A warm wind loosens the wings.

A butterfly lifts from the edge of a petal.

If I were a butterfly, how would I leave the edge of the petal?

The exhibition title, Petal’s Edge: Cutting into Spring, draws from William Carlos Williams’s poem “The Rose Is Obsolete.” The poem opens bluntly: “The rose is obsolete.” No longer bound inevitably to love or romance, the rose retreats toward the boundary of form—the petal’s edge. If cutting occurs again and again, how might edge and body reunite? How might form and meaning gather once more?

This question feels like the entrance to the exhibition. Thus I begin here: If I were a butterfly, how would I leave the edge of the petal?

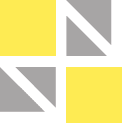

If I were a butterfly, my compound eyes would offer low resolution but heightened motion. I would navigate by dynamic vision, detecting light that slips behind objects. The first image before me: light falling across A Pair of Fritillaries. Their patterned petals shimmer. The flowers droop slightly. Their edges are not round but faintly sharpened. What draws me most is the depth of black at their core.

I imagine the maker’s gesture: a brush heavy with ink, a single decisive stroke. I leap from the edge of the petal. There, a thin ultraviolet sheen clings to the speckled surface—a guide only I can see. I extend my proboscis. No sweetness arrives. Instead, a mineral taste. No fragrance, only paper and ink, a faint scent like a scholar’s desk. Within the dense black, fine granules linger—traces left by ink resting overnight. I require minerals anyway. I do not mind.

I leave the fritillaries and drift toward Tulips Leaning Toward the Light. Tulips are rarely our first choice. Their buds hold tightly, difficult to enter. I land near the foremost vessel. An east wind carries the warm scent of sun. The tulips lean eastward, toward brightness.

Their leaves narrow gradually, yet unlike leaves I have known. No delicate veins. Their edges are uneven, almost blunt—as if the maker wielded a broad brush without fussing over turns. The tulips in the front vessel appear moist; those behind, slightly parched. Each holds its own posture.

Further back stand three empty vessels. In the wild, this would be strange—where there is space, something grows. Here, they are deliberately left unfilled. They do not rush to cradle spring. They simply occupy space.

This emptiness unsettles my flight. Instinct urges me upward, searching for hidden growth. Midair, I realize: this is a trap. Not malicious—only a quiet redirection. A station that interrupts the original path of flight.

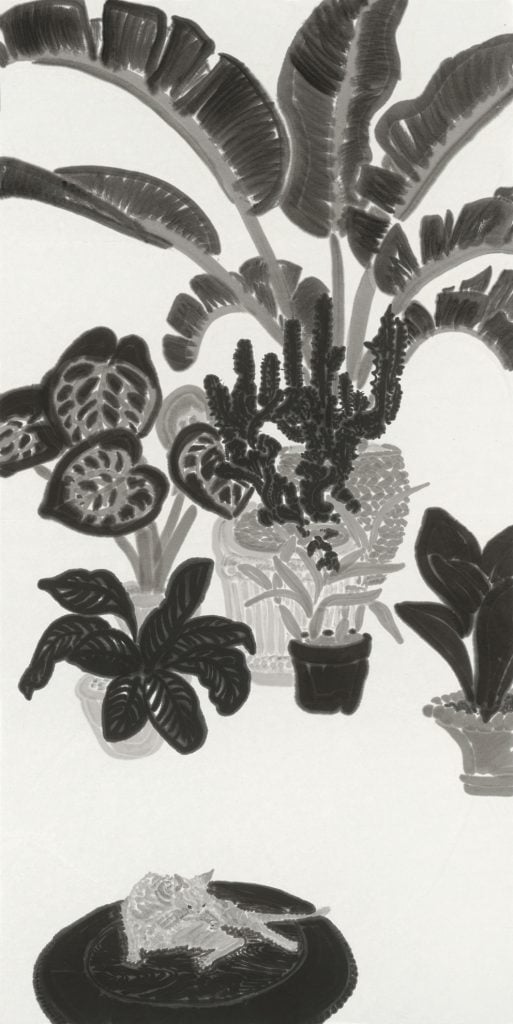

I enter Cat and a Roomful of Plants. The cat glances at me, then resumes grooming its pale gray fur. I hover between it and the plants. Its eyes narrow slightly, as though neither I nor the plants exist.

“Can you see me?” I ask.

No answer. Yet the ears tremble.

“Can you see the plants?”

The tail flicks. “Of course. Their edges are obvious.”

I look again. I see no sharp edges. Instead, fine grains hover across their surfaces. The alocasia’s veins resemble my own wings. Along the margins, a faint halo—like rain spreading across asphalt long after the storm has stopped.

I grow uneasy. Not because I cannot see clearly, but because this scene does not feel present. Eight shades of black against one white. Granules suspended, as if time has congealed. I cannot tell whether I am looking at this moment, or at an image already developed.

“Can you see me?” I ask again.

The cat does not respond. Even its ears remain still.

It continues grooming—yet it does not. Everything has stilled.

I retreat to the frame’s edge. Only the whisper of my wings remains.

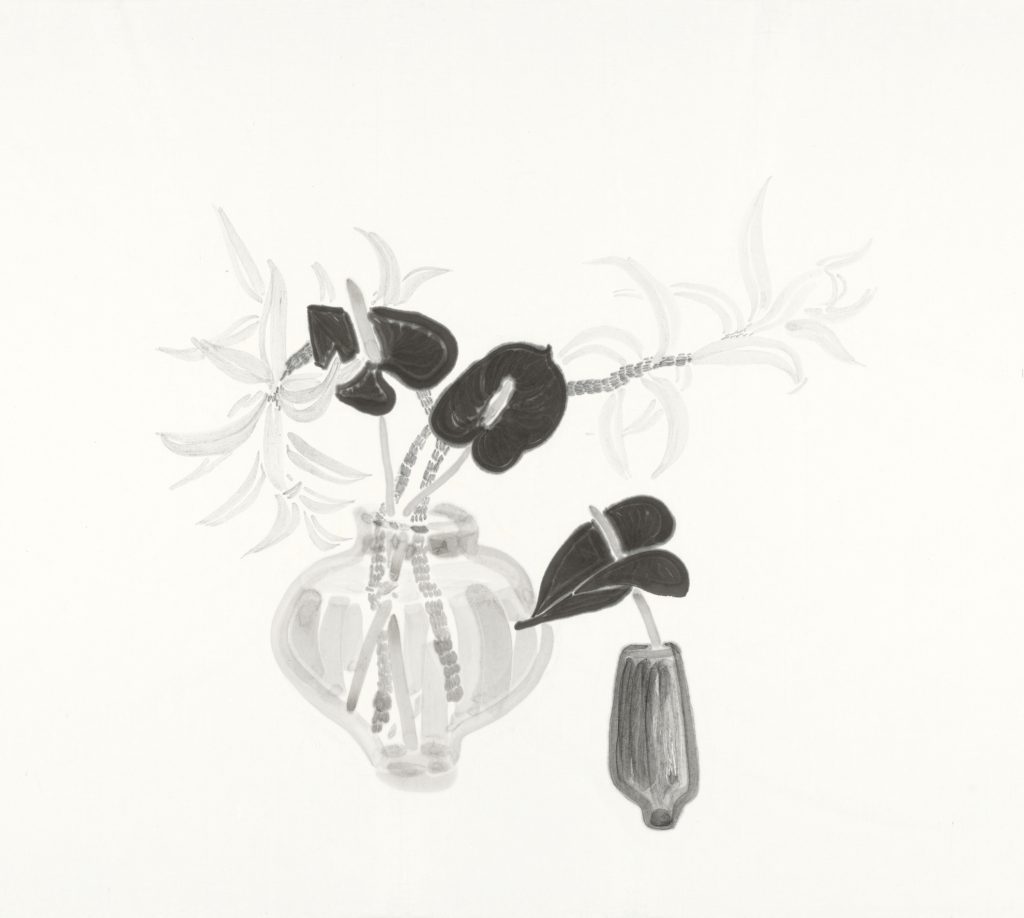

I move toward Anthuriums and Curved Dracaena. Anthuriums offer neither nectar nor scent, yet I admire their shape. Their lines are fluid, as though they might lift into flight. Three anthuriums form a plane: one tilting left, one frontal, one rising right. Two dracaena curve beside them—one thrusting forward, shifting the center of gravity; the other bending like a staff, enclosing space.

Nothing here feels forced. The maker seems to listen to the plants, allowing them to find a temporary alignment within light.

Their stems sink into water. Water receives them without rupture. I hover above the surface. The maker appears to have painted while the paper was still wet—ink spreading freely along its fibers, edges blooming into soft halos, watermarks unapologetically visible.

Moisture does not linger. Neither does light.

While there is light, I can see form, color, even the fine ultraviolet lines invisible to others. While there is light, I skim the petal’s edge. It appears sharp, yet not sharp enough to wound. It cleaves the air thinly, embedding itself into space.

I rest upon the edge. There is no pain—only cool dampness beneath my feet.

If I were a butterfly.

I enter Grand Herbs and Slender Woody Plants. I settle along a serrated stem. Broad leaves gather above; slender woody branches stretch below. Light slips through the leaves in layers, resting upon the thinnest, most fragile surfaces—upon the edge of spring itself.

Cold air.

Warm wind loosening wings.

I lift from the petal’s edge.

I leave the fritillary’s core carrying mineral dust.

I leave the tulip’s turn and pause beside the empty vessel.

I leave the cat and alocasia to witness motion held still.

I leave the rhythm of anthurium and dracaena to rest upon light.

Williams ends his poem:

“The fragility of the flower

unbruised

penetrates space.”

Cutting leaves no wound. Only the meeting of dry and wet. Only the trace of moisture flowing outward.

While there is light.

While the paper remains wet.

Spring unfolds there.

▞ Exhibition Information ▞

Title: Petal’s edge: Cutting Spring — Yuning Yang 2026 Solo Exhibition

Exhibition Period|March 7 (Sat.) – April 18 (Sat.), 2026

Opening Events|March 21 (Sat.), 2026.

15:00–16:00|Artist Talk Artist Yuning Yang × Discussant Hsiao Kai-Ching. 1

6:00–17:00|Opening Reception

——————————————————-

▞ Series of Events ▞

Exhibition Event|March 26 (Thu.), 2026

15:00–15:30|Ikebana Performance — Instructor Lung Kuo-Ying

15:30–16:00|Exhibition Tour — Artist Yuning Yang

Venue|San Art Gallery · Kaikosha

Opening Hours|Tuesday to Saturday 10:00–18:00 (Closed on Sundays and Mondays)

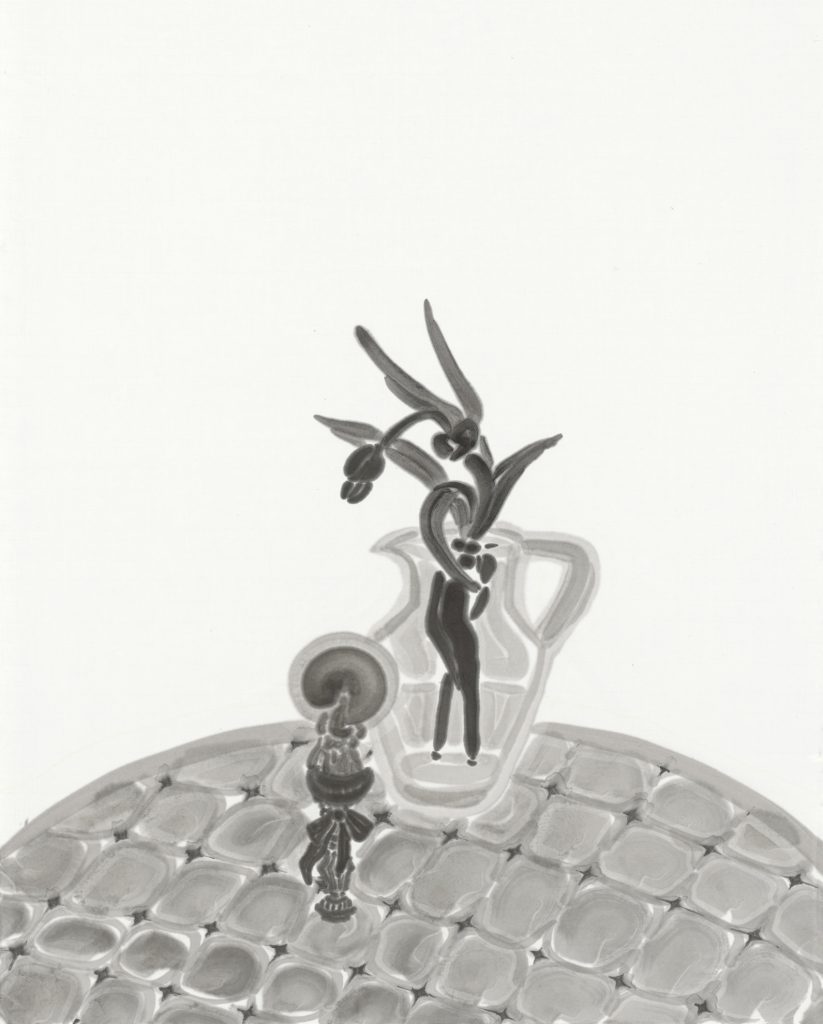

楊寓寧Yang Yu-Ning_一雙貝母A Pair of Fritillaries_墨水紙本Ink on paper_58x 38cm_2025

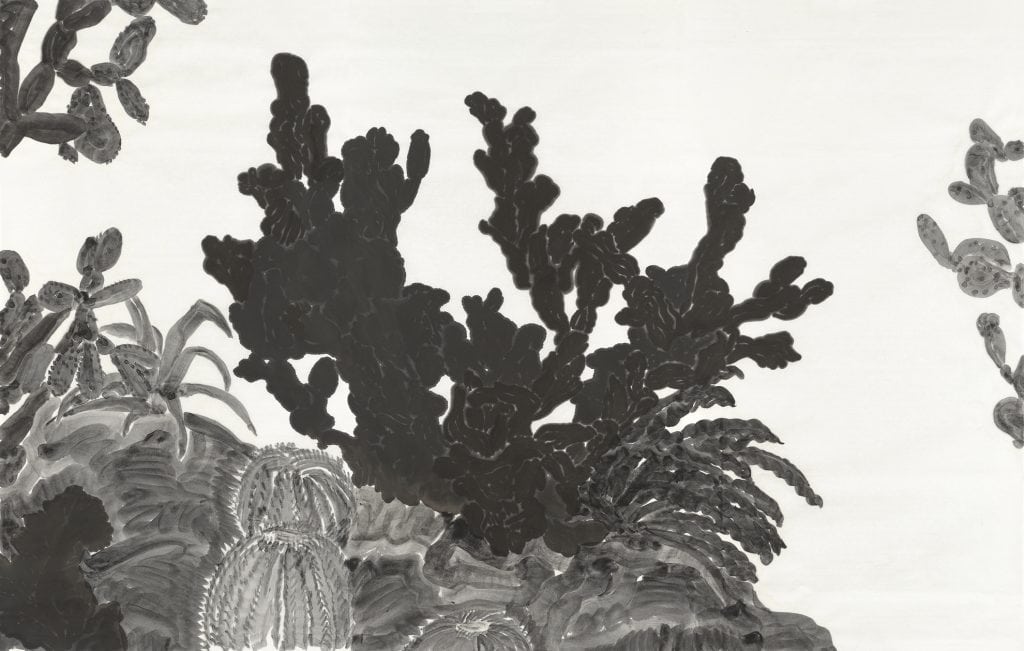

楊寓寧Yang Yu-Ning_苔球的序列Sequences of Moss Balls_墨水紙本Ink on paper_77.5x134cm_2025

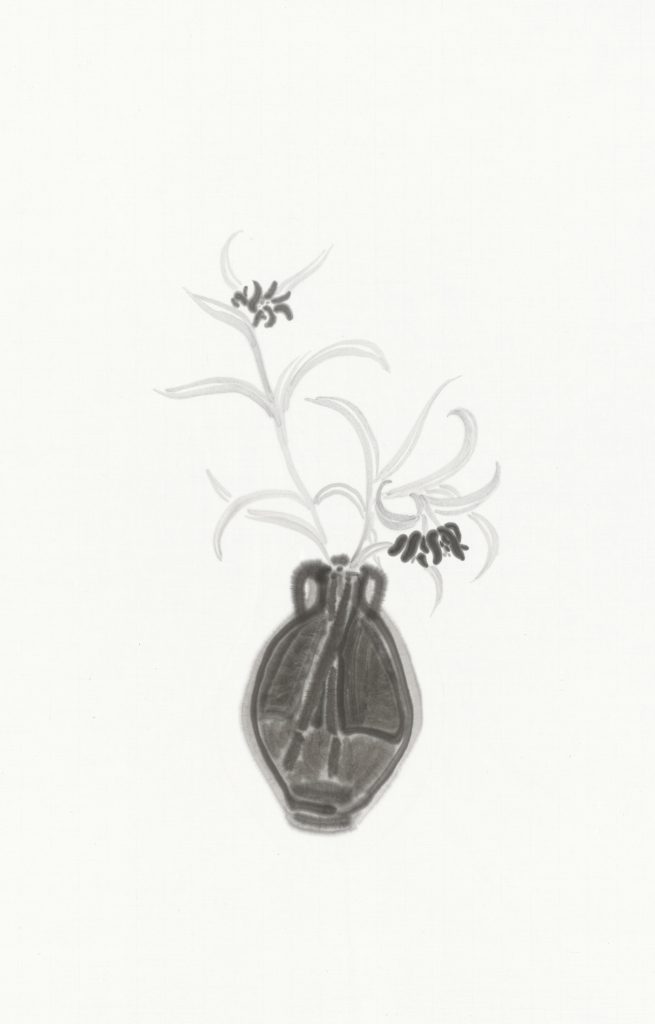

楊寓寧Yang Yu-Ning_舒展在溫室內Stretching in the Greenhouse_墨水紙本Ink on paper_181x281cm_2022

楊寓寧Yang Yu-Ning_用小花妝點松Adorning the Pine with Florets_墨水紙本Ink on paper_95 x60cm_2025

楊寓寧Yang Yu-Ning_向光斜倚的鬱金Tulips Leaning Toward the Ligh_墨水紙本Ink on paper_71.5x100cm_2025

楊寓寧Yang Yu-Ning_蠟燭、鬱金香與格紋Candle, Tulips, and Plaid_墨水紙本Ink on paper_90x 79cm_2025

楊寓寧Yang Yu-Ning_火鶴與彎曲百合竹Anthuriums and Curved Dracaena_墨水紙本Ink on paper_77.5×85.5cm_2025

楊寓寧Yang Yu-Ning_貓與一室植物Cat and a Roomful of Plants_墨水紙本Ink on paper_248x 123.5cm_2025

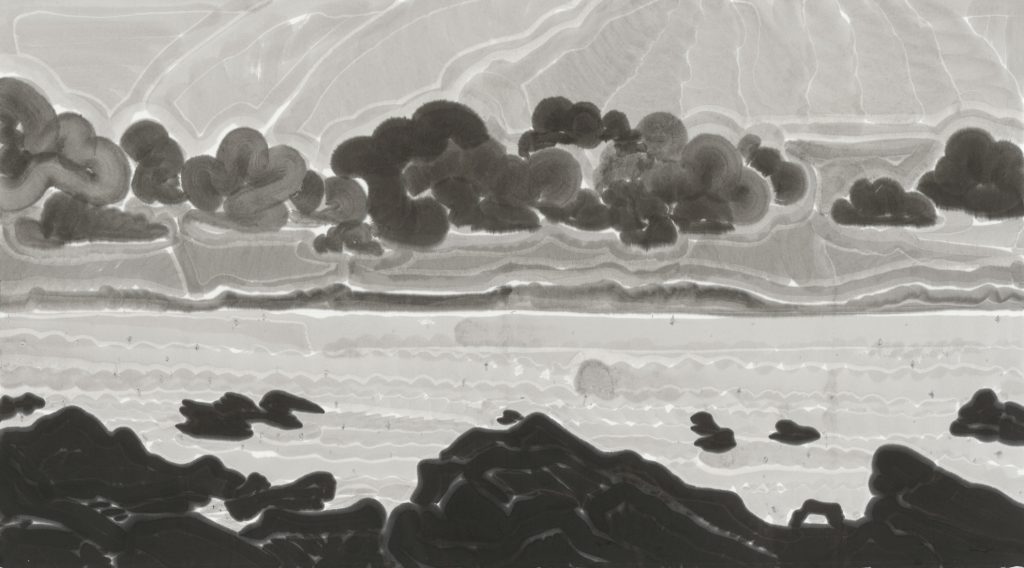

楊寓寧Yang Yu-Ning_海色Seascape Hues_墨水紙本Ink on paper_141x 79cm_2025

楊寓寧Yang Yu-Ning_巨大草本與細小木本Grand Herbs and Slender Woody Plants_墨水紙本Ink on paper_140.5 x 77.5cm_2025

楊寓寧Yang Yu-Ning_巨大草本與細小木本2Grand Herbs and Slender Woody Plants2_墨水紙本Ink on paper_98 x 91cm_2025